Krisis: A turning point

A wide variety of crises were discussed during the STOSO Congress titled ‘In case of emergency; understanding and managing crisis’. Dr. Lonneke Lenferink taught us a lot about ‘Grief after Loss in Disasters’ while Jamal Ezaarqtouni and his colleague brought it close to home and shed their light on social stability in our society. Alex Escalona addressed the issues around traumatized refugees. We could enjoy the same variety in the two rounds of four workshops. The Red Cross addressed Immediate Crisis in and around our house, Veiligheids Regio Groningen (VRG) let the participants work on Regional Crisis Prevention, Defensity College helped participants to understand the complexity of warzone decisions and Charmaine Borg showed how our own sexuality and sexual relationships sometimes put us for dilemmas.

George Parker & Dr. Lonneke Lenferink

Indeed, crises are very different in nature so let’s first explore the concept a little bit more so we can understand that crises are part of life and how we can use them to our benefit.

We tend to interpret a crisis as a negative situation but the Greek word krisis means ‘turning point in a disease, that change which indicates recovery or death’. The meaning evolved over time, but I think that the meaning of turning point is still very valid. We’re put in a situation (or sometimes we put ourselves in a situation) that develops to a moment of truth. When that moment arrives it requires us to stay awake, analyze, use our best judgement, make a decision and act accordingly. That is stressful because

- it will result in tiny or big changes that require us to adjust our ideas and behavior and

- because we only control part of the situation while another part is controlled by other people, circumstances or fate and we’re not exactly sure what part we can control or how we can control it.

In my mind this is true for all types of crisis. It holds up in a warzone situation that puts soldiers in a position that’s radically different from day to day life and that doesn’t give them full control over the situation. It’s also true for sexual relationships where we explore new things that require us to change, but we’re far more in charge. When fate strikes and the VRG needs to act we might have prepared our homes just like the Red Cross suggested, but for the rest we just need to wait and follow instructions.

I will elaborate on the first point (change) by describing some of the psychology I developed while experiencing the sometimes radical changes I put myself through. Then I will describe a reactive versus a creative attitude and how the latter can help us to get more control and put a positive spin on crises, especially the ones that are triggered by causes outside of us.

Change

Driven by efficiency

We are creatures of habit. That makes sense since we’re biological creatures that are wired for efficiency. Routines save a lot of energy so we install thinking patterns and behavioral patterns whenever we can. In the process we install and reinforce neural pathways in our brain on a biological level. On a psychological level we condition ourselves by installing fixed association patterns. The good thing about that is that we save lots of energy this way. We don’t have to discover our way home and we don’t need to spend time learning how to dress every single day.

Identification

The bad thing about creating those habits is that, over time, we tend to identify with the way we think and behave. We don’t see the patterns we installed as just useful patterns anymore. We’ve become so accustomed to them that it’s hard for us to see that there are alternatives to what we think and how we act.

Crises force us to rethink patterns

It happens in all areas of our lives: in relationships with family, friends and spouses. But also at work and in our hobbies. We tend to stick to routines that have served us well in the past. That’s wonderful as long as they work. But change will happen at some point. We might feel the need for change and start to act on it. Economic or political circumstances change or the people around us start to make different choices that affect our lives. Maybe a natural disaster occurs or the company you work chooses to go in a different direction. This will all result in some kind of crisis. Things are changing and there will be some pivotal points ahead that require us to rethink and maybe redesign our patterns.

Different grades of change

Mild changes like going on vacation with our family to a different but still quite familiar destination will not affect us much. But when we visit a completely different culture and circumstances and environment are wildly different from what we’re used to, we will need to get adjusted much more. We know that even on regular vacations there are some crises in the form of fights between partners. That’s because we let go of our daily routine and are suddenly together far more hours per day than we’re used to. Add a foreign culture and a strange environment to that and stress levels could be through the roof and smaller or bigger crises will occur. I remember a huge fight with my wife that came out of nowhere when we spend our very first vacation without our kids. We had been looking forward to that moment for a while. We didn’t realize we had to re-learn how to spend vacation together.

There are far more brutal changes that result in a crisis. When you need to leave your country you leave behind the land, but also the social context, the language and everything else that was familiar to you including the ‘bush doctor’ as mr. Escalona shared with us in an example. The changes are so big and you have so little control that you’re shaken to your core. It will take a much longer time to recognize what has happened and to get adjusted to the new situation. A bit of good news was that Dr. Lenferink told us that a majority of people who suffer loss are actually resilient and get through the crisis pretty well.

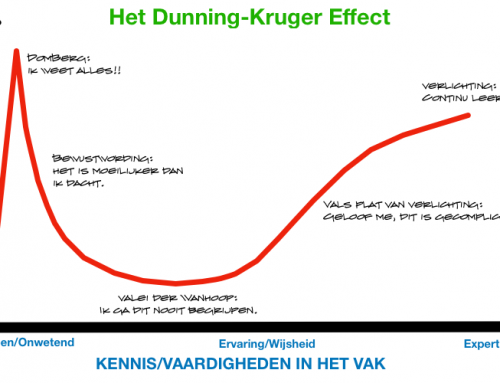

The ABC of identification

It’s not always an easy task to recognize our own patterns let alone to adjust them to deal with the changes at hand. That’s because the process of installing patterns happens over time. We fail to notice how we get used to these patterns and sometimes identify with them so much we think we are our ideas and behavior. It helps to realize that there are different levels of attachment to our own ideas and behavior. I will describe them as the ABC of identification:

A= Assumptions

B= Beliefs

C= Conviction (or Paradigm)

Minor crisis

Let me give you a simple example of how the progression from assumptions via beliefs to conviction might work. After we’ve been to a restaurant and had a steak, we will assume that the next restaurant we visit will also serve a steak. If it’s just an assumption and the restaurant owner tells you: “Sorry no steaks here, only cheesecake and wine”, you might be surprised for a moment but you will get over it pretty easily. It’s a minor crisis.

Bigger crisis

But when you’ve been to three dozen restaurants and they all confirmed the assumption (‘restaurant=steak’), the assumption turns into a belief. When that has happened and the restaurant owner tells you ‘Sorry, no steaks here.’, you might be quite upset and not be able to let go of your belief so easily. It feels like a bigger crisis because you have to dig deeper to adjust.

An even bigger crisis

Paradigms are beliefs that have sunk into our subconsciousness. If we’ve only experienced restaurants where they had steaks for a long time, we can’t even imagine a restaurant not serving steaks. Or we refuse to call such a place a restaurant. When the restaurant owner tells us they don’t have steaks, we’re beyond upset. We just can’t wrap our head around it and our response varies from blowing up to being completely stunned.

Control

Reactive and creative state of mind

The degree of the crisis we experience seems to be related to how much we identify with our habits. I’m sure some of you are convinced you can’t change habits or ‘you are just who you are and can’t do anything about it’. As a consequence, going through change means going through a nasty crisis that everything inside of you resists.

To me, the conviction that you can’t change anything, is nothing more than that: a conviction. I’m inclined to challenge my own assumptions, beliefs and convictions because I’ve always found it fare more interesting -and quite frankly more fun-, to see my own old ideas return to dust at some points in my life when change occurs. For example, I was always convinced I would never ever marry until I met my wife. A huge paradigm shift that I could defend with the same vigor I had defended my never-marry opinion. that just repeating the idea that nothing can be changed and being victimized by circumstances.

A creative state of mind

As a consequence of that attitude I chose to expose myself to lots of personal and professional changes in the last decades. I played and experimented and reinvented myself in my personal and professional life over and over again to see if I could bend myself and reality.

My starting point was that everything in the world, apart from nature, is the result of a human creative process. To create simply means to bring something into existence. It doesn’t matter whether it’s unique or common of beautiful or ugly. It doesn’t matter if it’s a thing, an idea or situation. These are all results of a process that brings something into the world.

Select any object around you and go back to its origin. You’ll discover that it started with an idea, an action, a feeling before it materialized. It can be something mundane as a sandwich or toilet paper. But maybe you’re looking at a smartphone, a car or your house. We also bring situations into the world; we create events, emotions, thoughts. Everyone of the things I just mentioned is the result of a creative process as well as part of another creative process. Starting with that axiom (that I refer to as a creative state of mind) early on in my life has helped me to discover that we have far more control over a situation than we assume.

A reactive state of mind

Assumptions tend to self-confirm. So the assumption that that circumstances define us, starts a process of selective perception. We tend to select information that supports our assumptions: “See, I couldn’t help that, it was out of my hands!” (and we make our point by adding some carefully selected facts and avoiding any facts that don’t support this idea). Before we know it we are incapable of seeing or hearing anything that doesn’t confirm our bias. After a while our head is filled with a selection of facts that proves our point; the belief has turned into a paradigm. We can’t help but see life, and ourselves through that lens. Again, this isn’t bad in itself. It helps us to save lots of energy. But when we feel an internal or external urgency to change, these paradigms can be a prison that causes a lot more pain and suffering than is needed.

Creative includes reactive

The creative state of mind includes the reactive state of mind and not the other way around. From a the creative paradigm the reactive state of mind is just another thought pattern; another perspective that can be used in certain situation. The creative mindset isn’t attached to a certain belief or paradigm. It looks at ideas and behavior as a painter looks at colors. Colors don’t have any meaning in themselves. We can use them to materialize our visions on the canvas. Just like we can use certain ideas and types of behavior to help us realize the life we want.

Reactive tends to exclude creative

That’s not the case in a reactive state of mind. The reactive state of mind will resist anything that threatens its status quo. It refuses to even look at the creative state of mind as a valid option: “Get real! You can dream all you want, but real change will never happen.” It wants to glue us to one belief or one type of behavior and repeat it forever. In the process it tends to ignore the facts of life or even denies them. It has a hard time remembering the paradigm shifts that happen throughout our lives. For example, imagine yourself before and after puberty, before and after your first kiss, your first job, your first public speech, your first vacation on your own, your first break-up, your first (fill in the blank). If we would be able to record what’s going on in our minds and bodies before and after a pivotal point in our lives, we could easily see our ideas and behavior changes all of the time.

Life and work as creative projects

Living and working in a creative state of mind means that you look at life and yourself as a creative project. You expect crises to be part of any change you go through. For example, when you envision riding a bike you know it will take trial and error to master that skill. You expand your old skillset to realize your vision. You adjust the way you think about transportation. When you’ve gone through many of these self-imposed crises, you start to recognize that you’re a constantly evolving, changing human being. You will feel increasingly free to envision anything you want and won’t shy away from pursuing that because crises are part of that journey.

Crisis as a circumstance and a chance to increase awareness

As a result of that attitude and these experiences you will also deal with crises that aren’t under your control much better. You will have explored your own influence on what you think, how you behave and your decision making process. And you will have become aware of the fact that, on a sailing boat, you can’t influence the wind but you are able to adjust your sails, handle the rudder to get to your destination and expand your skills to become a better sailor in general while you’re making the trip.

In a reactive state of mind the crisis tends to define us. In a creative state of mind, we frame the crisis with our vision. We regularly envision ‘memories of our future’. In other words, we fantasize about experiences, events and relationships we’d love to see happen in life. We have strong feelings, clear pictures of that vision. When fate throws something in our lap, it won’t affect our deepest visions so much. We stick to what we want our lives to be and are willing to swap ineffective ideas and behavior for better ideas and more productive behavior.

We know that more than one crisis will occur along that path. These are welcomed as moments of truth, just like the original meaning. They are crossroads requires us to you to stayt awake, analyze, use our best judgement, make a decision and act accordingly. Not based on what we think life was and is, but based on our vision of what we want life to be. The more you have experienced you’re a natural problem solver and you can use it to create a way to realize your visions, the more resilient you will be.

George Parker

+31 6 5110 8415